Latin Mass in the Extraordinary Form has been something I’ve always wanted to experience and assumed I would love. I am a Catholic who revels in the traditions and rituals of the faith. I love candles and stained glass, incense and statues. I attribute a lot of that to the fact that I was raised in what I like to call the “Era of the Collage.” By the time I got to CCD class, as it was known back then, tradition and catechism had gone out the window, only to be replaced with gluing and pasting pictures of a smiling Jesus and the word “love” on construction paper week after week. I hungered for the “bells and smells” of the past, something that was a staple in the faith of my family of origin. (My godfather still goes to weekly Latin Mass in Virginia, so this stuff is in my DNA.)

This weekend I finally got my chance to step back in time and experience the Mass as it once was, when Bishop Edward Scharfenberger of Albany celebrated Latin Mass in the Extraordinary Form for more than 300 people at the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception.

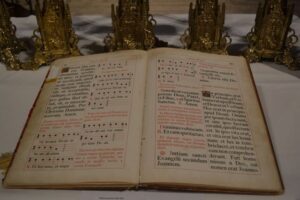

As we waited for Mass to start, we watched families filing in, many of the women and girls wearing head coverings and  quite a few men and women carrying missals. The already magnificent cathedral was even more beautiful with the altar set with a row of large candles and an ancient-looking Latin sacramentary.

quite a few men and women carrying missals. The already magnificent cathedral was even more beautiful with the altar set with a row of large candles and an ancient-looking Latin sacramentary.

Mass itself was an education for me; it’s really something I think every post-Vatican II Catholic should experience at least once, if only to understand the history of the Mass and perhaps why it was so difficult for many people to accept the changes. And why the changes were made in the first place. What a dramatic shift for adult Catholics of the 1960s. It’s hard for me to imagine what it must have been like to go to this form of the Latin Mass for most of your life and then walk into church one week and find everything — from the language to the altar arrangement to the form of the Mass — changed, even if the substance remained the same.

Although I found the Mass to be beautiful and somewhat mysterious (in a good way), I have to admit that I felt a spiritual disconnect. I have no problem whatsoever with the priest facing away from the congregation. I’ve been to Masses celebrated that way in Rome and actually kind of like it. But in the Extraordinary Form, the celebrant spends so much of the Mass praying quietly to himself in Latin that it felt as if I was intruding on someone else’s private prayer. Even during the Eucharistic Prayer, I didn’t know the moment of consecration had arrived until I heard the bells. I suddenly understood why so many Catholics prayed the Rosary throughout Mass back in the day; there is so much silent time when congregants are just sitting or kneeling in anticipation of the one line or half-line they are allowed to say that people must have needed

Although I found the Mass to be beautiful and somewhat mysterious (in a good way), I have to admit that I felt a spiritual disconnect. I have no problem whatsoever with the priest facing away from the congregation. I’ve been to Masses celebrated that way in Rome and actually kind of like it. But in the Extraordinary Form, the celebrant spends so much of the Mass praying quietly to himself in Latin that it felt as if I was intruding on someone else’s private prayer. Even during the Eucharistic Prayer, I didn’t know the moment of consecration had arrived until I heard the bells. I suddenly understood why so many Catholics prayed the Rosary throughout Mass back in the day; there is so much silent time when congregants are just sitting or kneeling in anticipation of the one line or half-line they are allowed to say that people must have needed  something to fill that void. It was either say a Rosary or risk getting caught up in a daydream or looking around the church. There may be those Catholics who are so adept at silent contemplation that perhaps they are able to enter into that place in the midst of the Latin Mass, but I have not yet reached that spiritual plane. I found myself struggling to stay connected and thankful, after all, that I am a post-Vatican II Catholic.

something to fill that void. It was either say a Rosary or risk getting caught up in a daydream or looking around the church. There may be those Catholics who are so adept at silent contemplation that perhaps they are able to enter into that place in the midst of the Latin Mass, but I have not yet reached that spiritual plane. I found myself struggling to stay connected and thankful, after all, that I am a post-Vatican II Catholic.

I was so grateful for the thoughtful homily delivered by Bishop Scharfenberger, giving me a few minutes to reconnect, and for the recessional hymn — in English and familiar. Yes, it was all very beautiful but it was also all very foreign. I have new respect for St. Pope John XXIII for having the courage to initiate the changes that led to a Mass that is so much more accessible. I found myself frustrated that not only wasn’t I able to say the Our Father in Latin, only the last piece of the last line was ours to say. And even at Communion, kneeling and received on the tongue for the first time in a very long time, I was not able to say “Amen.” It made me feel like an outsider looking in, and I’m not used to feeling that way in church.

I think it’s wonderful that the popes of our day allow this Mass to be celebrated — and that it was celebrated in a diocesan cathedral by a bishop, a rarity these days — but I now know that my Catholic feet are firmly planted in the spiritual here and now. My brief time travel back into our Catholic past was interesting and enlightening, but there’s a reason we shouldn’t live in the past permanently, and there’s a reason things change with time. I try to imagine the world born of the 1960s, 70s and beyond co-existing with this liturgy, and what I see instead is an even greater hemorrhaging of Catholics than we experienced at the time. The Extraordinary Form may be beautiful in its exterior trappings and historical importance, but perhaps it is too extraordinary for ordinary Catholics who want to be fed in a way that speaks to them — both literally and figuratively — and challenges them to become active participants in the liturgy and the everyday faith that grows out of the Eucharistic experience.

I think it’s wonderful that the popes of our day allow this Mass to be celebrated — and that it was celebrated in a diocesan cathedral by a bishop, a rarity these days — but I now know that my Catholic feet are firmly planted in the spiritual here and now. My brief time travel back into our Catholic past was interesting and enlightening, but there’s a reason we shouldn’t live in the past permanently, and there’s a reason things change with time. I try to imagine the world born of the 1960s, 70s and beyond co-existing with this liturgy, and what I see instead is an even greater hemorrhaging of Catholics than we experienced at the time. The Extraordinary Form may be beautiful in its exterior trappings and historical importance, but perhaps it is too extraordinary for ordinary Catholics who want to be fed in a way that speaks to them — both literally and figuratively — and challenges them to become active participants in the liturgy and the everyday faith that grows out of the Eucharistic experience.

I am grateful that my family fostered in me an appreciation for the traditions of our faith. While I made felt banners and homemade hosts as the teen-age president of CYO at my parish, I also attended daily Mass and prayed novenas and rosaries. I grew up with a blend of old and new, and I think that’s a good thing. To this day I prefer a Mass that includes the Greek Kyrie Eleison and the Latin Agnus Dei right alongside a St. Louis Jesuits song. In fact, Dennis has been instructed to make sure Agnus Dei is sung at my funeral Mass, whenever that is. And Panis Angelicus. I will always appreciate the traditions of our Catholic past, but I am ever so grateful for the reality of our Catholic present.